A few years ago, I had the great fortune to be introduced to one of the most interesting and experienced outdoors people I've ever met, Quebec's André-Francois Bourbeau, also known as "Dr. Survival!"

Much of Dr. Bourbeau's work is in French, and I think because of this, he is not well known in the U.S. outdoors community; but, his work and story are fascinating, and we’re excited to introduce our readers to Dr. Survival!

Photo courtesy of André-François Bourbeau.

Learning the Outdoors

You have a PhD in survival education. Could you describe your outdoor educational path, both formal and informal?

After my Master’s degree in Outdoor Education at the University of Northern Colorado, I wanted to pursue work in survival education, which did not exist at the time. Through the School of Educational Change and Development, we were allowed to prepare our own doctoral program as long as seven professors accepted it. I proposed four 10-day survival trips, one in each season, plus travel to spend time with primitive tribes in foreign countries, plus classes in many different departments of the university, such as lithic technology, native history, advanced systematic botany and so on. Of course, I had to write a thesis on survival education.

Informally, survival skills were a passion. In the days before Internet, I had to build my skills by experimentation, having no one to show me. For example, I worked for two years on fire by bow drill without success until one day I happened to try it on a board which had a natural crack. That’s how I found out a notch was needed! Some of the lessons were hard (like the time I took a giant bite of Indian Turnip root, which contained sharp calcium carbonate crystals—I thought I was going to die!).

Photo courtesy of André-François Bourbeau.

Did you have any special outdoors mentors? Any favorite books on the subject?

Like I said, I did not have any mentors at an early age; I learned on my own, but through a systematic approach. I would voluntarily leave out equipment on camping trips. For example, I would go out without any rope of any kind, no straps, no belt, no shoelaces, no extra cloth, nothing to make cordage. That’s how I learnt which plants and tree barks would make good string.

Later, I found many mentors, such as Kirk Wipper, Taylor Statten, and Harlan Gold Metcalf. Later still, I was lucky enough to spend time with native friends Gérard Siméon and Jimmy Bossum, elders from another era.

My favorite books in the subject, no surprise here, are the ones which relate real survival stories. Just about every real-life account of historic expeditions count, be it Franklin, Hearne, Shackleton, Fraser, or any of the other explorers of that era. Also, first person accounts of disasters, for example Steven Callahan’s, Adrift, or the story of the Andes survivors. In my opinion, popular survival books are most often hardly worth reading, especially the ones without photos.

Your book, “Wilderness Secrets Revealed, Adventures of a Survivor,” is fantastic! "Surviethon – 25 ans plus tard," your other book, is in French. Will we ever see it in English?

Waiting for you to translate it, Scott!

Teaching

You founded the first ever degree in Outdoor Adventure and Tourism at the University of Quebec, Chicoutimi, and also the Outdoor Research and Expertise Laboratory. You also founded a research laboratory on primitive technology at the University of Quebec. I think if I’d known about these programs, I’d have likely been packing my bags for Quebec when I headed off to school! What is it like for a student in this program?

Photo courtesy of André-François Bourbeau.

The Bachelor program I founded with my colleague Mario Bilodeau was, indeed, rather unique. Only 24 students per year were accepted, and the program was divided into three years with two sessions with three-month spells of non-stop field work. In the first year, students learned the intricacies of outdoor life: Summer and Winter camping, orienteering and navigation, first-aid, expedition cooking, and so on. During the second year, they delved into specific skill sets in the various activities: canoeing, kayaking, climbing, back-country skiing, dog-sledding, mountain biking, search and rescue, winter camping, and so on. The third year is dedicated mostly to outdoor leadership and project management, including therapeutic and scientific applications.

To finish the program, the students have to organize, finance, and participate in a major special project somewhere around the world. Some of the expeditions involved climbing Mt. Mckinley, trekking the Annapurna, canoeing Equador rivers, skiing Ellesmere Island, kayaking the Baja coast, biking to the tip of South America, surfing the Great Barrier reef, traversing Mongolia on horseback, and so on.

You developed a course on “Realistic Wilderness Survival.” What do students learn in this course?

Real survival is no tough guy game as shown on reality TV shows. On the contrary, real survival is when your life is on the line. Real survival depends on the balance between the difficulties one faces (e.g., weather, terrain, psychological duress) and the resources one has to deal with these difficulties (e.g., equipment available, generosity of the environment and people skills in four spheres: physical, mental, technical and decisional). To keep the balance positive, all we can do is plan ahead of time (prevention both in terms of equipment and choice of activities that match people skills) and build our strength in each of the four spheres. Notice that technical skills are but one aspect.

In the realistic wilderness survival course, students are taught how to survive a night in the forest while waiting for rescue, in a realistic setting, with just the clothes on their backs and what they normally carry in their pockets. Like in a real situation, they are dropped solo in the wilderness just a half hour before dark, after a full day of active outdoor activities, so they are tired and hungry. Prior to this, they receive training and demonstrations of what to do.

What essential skills should an outdoors person have before venturing into the wild? What minimum equipment do you recommend?

You might be surprised at this answer. The most important skill is the ability to plan a trip so it's level of difficulty matches people competencies and equipment available—and the humility to ask other leaders to validate this prior to departure.

As far as equipment is concerned, by far the most essential piece of gear in this day and age is a satellite emergency locator beacon, such as SPOT. I know this is not a sexy answer, but it’s what will save your life.

I don’t believe in survival kits because you won’t have them in a real situation. What you will have is what you normally carry in your pockets. So check your pockets as you read this; I promise you that is all you will have in an unexpected emergency. That’s why I carry my pocket knife, Bic lighter, ferrocerium rod on key chain, and other small pocket gear at all times, 365 days a year.

Dr. Bourbeau was the keynote speaker at the 2019 Global Bushcraft Symposium.

Photo courtesy of André-François Bourbeau.

Protecting the Environment

You talk not only about wilderness survival, but also survival of the wilderness. It’s clear that you are passionate about protecting wild areas.

It seems obvious to me that humankind is attempting to destroy all remaining wilderness for profit. Even the oceans and the remaining parks are no longer immune. Each and every one of us who cares about the environment and the wilderness has a role to play so that future generations can also experience nature as we have. I have talked about this at length in my books. Any project that proposes to encroach on existing wilderness should be regarded with much suspicion. Instead of looking for new land to build on, we should be looking at modifying existing developed land.

Many people I know who have been trained in Leave No Trace (LNT) would surely object to building bark canoes, natural shelter lean-tos, burning large, long log fires, and other primitive and bushcraft techniques. Some object to any fire, even in a northwoods environment. You mention in your book that you are a Leave No Trace Master Educator. Is there a reasonable balance? Can a woodsman use and consume natural resources in an environmentally responsible manner? Do you have any guidelines you recommend for those who enjoy a traditional approach to wilderness living?

Unfortunately, some LNT advocates are much too extreme in their views. Humankind has always used nature to survive. In fact, each and every item of everyday life uses nature, be it in the form of mines, oil, or agriculture, including forest agriculture. The computer I’m typing on comes from nature—bauxite mines to create the aluminum, oil derivatives to make the plastic for the wiring and keyboard, etc.

My thinking is that there are two underlying principles to the LNT movement. One is to respect the capacity of nature to renew itself. The other is to respect other users of the environment. A good example of this is the use of dead vs. green wood. In one situation, I observed an entire forest of many square kilometers of green firs, in which there were but a few sparse pieces of dead ash trees. Students immediately reached out to pick these dead trees for firewood, and soon they were all gone. This is not right. One guiding principle should be to only collect from nature what is really abundant. Better to take one in a million live trees than one out of three dead trees.

The location of what you take is also important. It’s easy to gather all you want from under hydro lines, they will cut everything growing there eventually anyway.

In established campsites, cleanliness is the important factor. But in the backwoods, any trace of passage should be eliminated, because others like to witness the natural environment as if they were the first there, too. In the backwoods, bringing a fire pan and burning only small wood is the single most important action you can take.

Photo courtesy of André-François Bourbeau.

I always conduct survival experiments in areas that will be clear cut the following year. In these locations, you are free to experiment at will without worrying about environmental impact.

I have no qualms about taking material from the environment, as long as it is absolutely plentiful, and as long as the next person to come along does not see where you took it. I built my entire house using trees from my own land. People walk right over spots where I removed huge trees, without ever knowing, since I removed the stumps and leveled the ground. Of course when I picked the trees, I was taking just one out of a clump of several. So you see, it is possible to consume natural resources in an environmentally responsible manner.

Reality TV Survival Shows

Dr. Bourbeau, you hold the Guinness World Record for the longest voluntary wilderness survival episode. Can you tell us what this is all about?

Back in 1984, I conducted a scientific experiment that consisted of being dropped by helicopter in the middle of the northern boreal forest without gear of any kind for 31 days. No matches, no knife or tools, no food, no shelter, and especially no bug net or repellent. Just plain city clothing. The spot was chosen by tossing a dart on a map, which ended up being in a swamp with the most serious black flies I had ever seen. It had just stopped raining, everything was soaking wet, and the temperature was near zero Celsius. I had no idea that adventure would later be inscribed in the Guinness Book of Records!

What do you think of Bear Grylls?

Bear is very good at what he does—entertainment; however, following his footsteps in a survival situation would be very dangerous. You see, in a real survival situation, you have four jobs to do:

Signal your presence to Search and Rescue teams.

Save your Energy and, if possible, renew it with water, food, and sleep.

Reduce Risks at all costs by slowing down and avoiding actions like climbing, jumping, crossing rapids, and eating crap.

Protect your existing Assets with actions such as tying up your knife, avoiding ripping up and dirtying your gear.

Photo courtesy of André-François Bourbeau.

This is the scientific SERA model I developed. In a survival situation, every single decision should be based on the impact the decision has on the four SERA factors. In Bear’s shows, for entertainment purposes, he is constantly doing the contrary and infringing on these rules.

What about the Naked and Afraid series? What are your thoughts?

We can actually learn a lot by watching this reality show, if we look beyond the sensational. Note how the lack of food makes them lethargic. Note also how they freeze because they do not know how to use fire for warmth; they should use the rottenwall and park bench technique I presented above, or the firebed technique (sleeping on top of buried coals). But more importantly, I agree with Mors Kochanski in that your most significant survival gear is the clothing you wear, and they have none. Making clothing would be my first priority; it is the first shelter you need. Watch how they suffer from bugs and sunburn!

Another popular series is Alone. Would you like to do this?

The main difficulty with the situation presented in this series is loneliness. There is also the food issue, which the contestants have trouble with; like I said above, this is not so easy unless you can hunt large game, and even then, the monotony of the food comes into play. Note how much weight the winner of season one lost.

The camping part of the ordeal would be child’s play to me. But I’m not at ease with spending time alone, I’m far too social minded, so I would not enjoy the experience. It would be a really difficult challenge for me.

Real Survival Skills

Photo courtesy of André-François Bourbeau.

Do you always practice primitive skills, or do you sometimes use modern equipment?

I do both. My trips are thematic. Two years ago, as a scientific experiment, I did a two-week trip in a spruce bark canoe and authentic period gear and food. I also did an 800 km trek along the Horton River to the Arctic Ocean in ABS canoes with Goretex clothing.

*Dr. Bourbeau has partnered with Billy Rioux, another French Canadian outdoorsman, for these trips.

Do you think it is important for a regular outdoors person to simulate survival situations and practice different techniques?

Like I said, once the survival situation presents itself, you will be faced with the survival balance. At that point, if your competencies and gear available outweigh the difficulties, you live; otherwise, you die. So anything you do ahead of time to prepare will serve to let you survive greater difficulties. But there may always be a situation in which the difficulties will outweigh your capabilities, no matter how good you are. That is why prevention is so important. The real value in practicing with simulated survival situations is that you understand more clearly the challenges of facing such events, and you become aware of the necessity of prevention. It’s like backing up your computer—you don’t learn until you’ve lost all your data at least once. Another example: try lighting a fire with a car cigarette lighter. After you stumble trying this for a couple of hours, even if you finally manage it, you will toss a Bic lighter in the glove compartment, guaranteed. So practice leads to prevention, which is why it is so important.

Photo courtesy of André-François Bourbeau.

You’ve got some great stories about your early adventures and misadventures in outdoor leadership. You’ve also described to me, and mention later in your book, your studies in risk management. Would it be safe to assume that your outdoor style has changed or evolved given your study of survival and risk management?

As we grow older, we become more aware of how quickly an accident can happen or a situation can deteriorate, and realize how very lucky we were in some circumstances that there were no consequences to our foolishness. Adventure is when things happen that you don’t expect. When you analyze every possible pessimistic scenario and prepare for it, then only things you expected to happen occur, so adventure becomes rare. But it is still fun to repair a broken paddle or have to build a new one, even if you expected it and brought along your crooked knife.

What do you recommend people do to develop their chances at survival?

Your capacity to survive depends on four factors: physical fitness, psychological outlook, down-to-earth techniques, and decision making. So, to help yourself survive a catastrophe, you must improve each of these.

Getting and staying in shape is one of the most important things you can do.

For psychology, the best aid is to read first-hand accounts of real survival stories, such as Jose Alvarenga’s 438 Days Lost at Sea or Dillon Wallace’s, Lure of the Labrador Wild. Then, if ever you are facing a real survival ordeal, you will have a point of reference knowing what other people have been able to endure.

Techniques are best developed by challenging yourself in simulated survival situations in a safe setting. I think one of the best exercises is to go out in nature and challenge yourself to simply fall asleep. This is easy when it’s nice out, but gets much harder when it’s cold or rainy or buggy, believe me.

Decision making can also best be practiced by simulations. Even paper and pencil exercises are valuable here, especially when discussed with others. For example, if you only had one choice of gear for long-term forest survival, what would it be? A knife? An axe? A ferrocerium rod? A Bic lighter? A pot? A tarp? A sleeping bag? I would choose a shovel. Why? Because I could sharpen it into an axe/machete, boil water in it, dig with it, and eventually cut a piece of metal off of it to make a knife.

Photo courtesy of André-François Bourbeau.

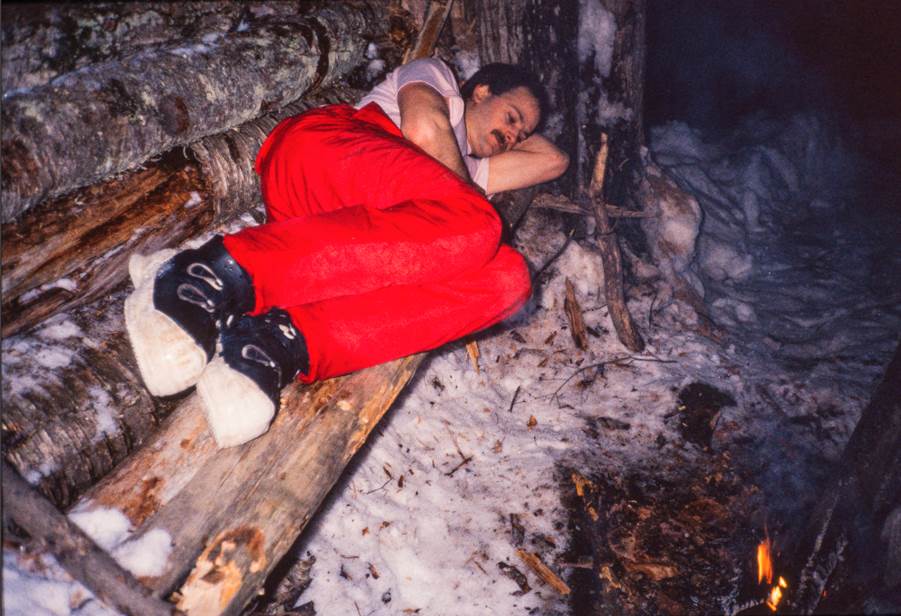

You penciled out for me your design for a survival lean-to (rotten wall and park bench). You listed several key details and intricacies; clearly, you’ve spent many nights in such shelters. Could you sketch out your lean-to instructions again?

Yes, I have easily spent hundreds of nights in such shelters, and I always make them the same way now. Check out this picture, which will give you the general idea:

There are indeed several technical points to notice here. Wind direction is from left rear diagonal. Bench is at knee height so heat goes underneath (many ways to do this, easiest is to put two long, weighted poles perpendicular and on top of the second log of the wall). Leave a space between the bench and wall, so heat comes up the wall and heats behind you. Wall is built to chest height with rotten logs and chinked with moss until it is airtight. Fire is exactly two meters from wall and level with knees to avoid smoke in face. Long logs with ends protruding from fire so you later get short logs to stuff between the long logs and get the fire roaring again. Set up is always so wind is from left rear diagonal because of heart position most people prefer sleeping on left side and also we are right handed so it is possible to manipulate (without getting up) the hooked stick (not shown) which is used to adjust the fire. Note the large tree positioned near the head which gives wind protection and creates a natural roof. Note also the extra log leaning vertically besides it creating a wind fence. This log can be removed (or others can be added) if the wind shifts, to control the smoke. What is not shown on the picture (for clarity) is the two poles leaning diagonally against the wall, which become the framework for the roof.

It’s often said that someone can go 30-40 days without food. Based on your research and experience, is food important? Should people work to learn about wild edibles and primitive trapping, fishing, and hunting methods?

Sure, you can go a long time without food, but just watch any of the survival shows on TV and see how people become lazy and nonchalant without food. This is a normal reaction because without food, the body goes into survival mode and no longer wants to work. Just a couple of days without food and you become extremely lethargic, not much gets done, and even brain function is affected. In cold, it’s even worse because without food, it is extremely difficult to fight off hypothermia and this can kill you. So the answer to the question is yes, learning all these food gathering skills will help, but realistically will not change the survival balance much in the short term. Unless you are very lucky, it takes a great deal of skill and very long training to obtain significant calories from nature.

Speaking of food, you’re a chef, and your father was a Master Chef. We love to eat great food while out camping! Do you have a favorite trail recipe you could share with us?

Like most chefs, I don’t use recipes, I cook from principles. Here are a few examples. Spices are lipo soluble, not hydro soluble—their flavor develops when heated in oil, not in water, which means each time I use spices, I fry them in oil first.

Photo courtesy of André-François Bourbeau.

Fresh onions will keep forever on trips and are the single most important flavor in all of cooking, but they must be fried to remove the sulfates which taste so strong. Try this: boil a chopped onion, two cups of water, a pinch of salt and a tablespoon of butter for half an hour. This will taste like dishwater. Take the same ingredients and fry the onion in the butter until dark brown, then add the salt and water. You’ve created French onion soup. Using this principle, start each of your habitual camping meals by frying an onion until dark brown, then continue as before and taste the difference.

Use the two principles above to make curried chicken. Fry onions in butter slowly until light brown. Add a good dose of curry powder and fry some more. Add salted chopped chicken and fry with onions and curry until cooked through and onions are dark brown. Add cream to make a sauce.

So you see, my recommendation is to learn principles and forget recipes. Even in baking, there are some basic proportions, which once memorized, let you prepare most anything without a recipe. For example, for bannock or pancakes or cakes, in one liter (four cups) of flour, the proportions are one teaspoon of salt and four teaspoons of baking powder or one envelope of yeast. Other ingredients, such as sugars or milk or eggs, are infinitely variable. If using yeast, just keep the temperature of the dough below 115 degrees Fahrenheit and wait for the dough to rise to it’s maximum size (double the original) before cooking, no matter how long that takes.

Principles of cooking can be learned by asking a chef or by reading the beginning of a good cooking manual.

Exploring the World

What is your favorite way to enjoy the wild these days?

I’ve been having fun designing and building small sailboat campers from plywood. Last winter, I crossed the entire Everglades through the Nightmare passage in a 4x8 boat, staying 11 days in it without getting out. I’m currently off solo sailing the Albemarle Sound, and I am planning to cross Mongolia by canoe next summer.

Mors Kochanski is a legend in the outdoor survival world. After studying his books and movies, taking his courses, and working with him, I put together a list of my top 10 takeaways from Mors.